The definition of e-waste or WEEE

Before exploring the waste, let’s clarify the E-s. In the European Union, electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) is defined as “equipment which is dependent on electric currents or electromagnetic fields in order to work properly and equipment for the generation, transfer and measurement of such currents” — in general, devices with circuitry or electrical components and a power or battery supply.

Once such a product no longer has value for its user or can no longer be used for its originally intended purpose, it becomes waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE), more commonly known as electronic waste, or e-waste.

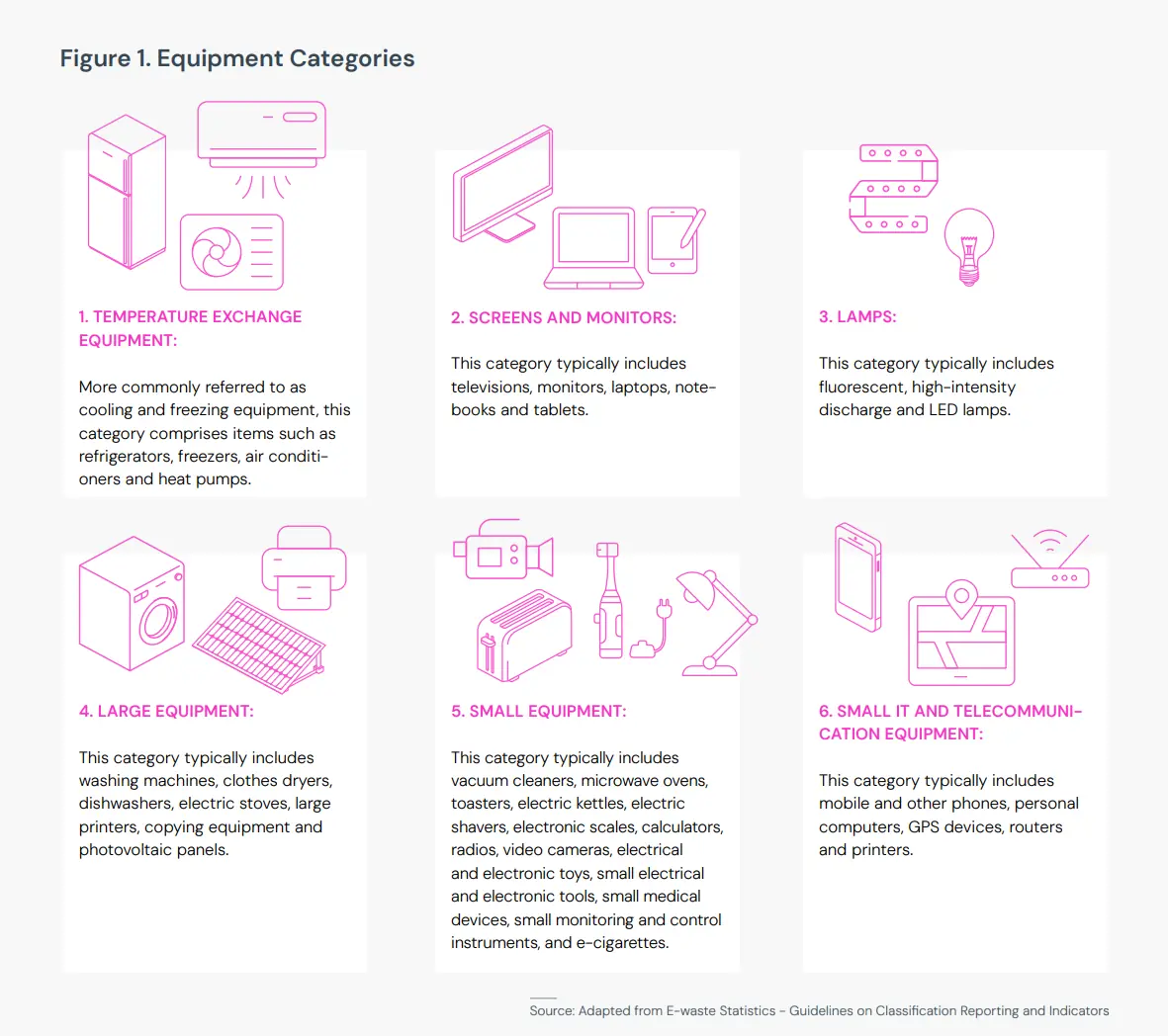

According to the products’ waste management characteristics, The Global E-waste Monitor 2024 differentiates between 6 general categories for e-waste:

These devices contain precious metals and critical raw materials such as gold, copper, aluminum, and other finite resources. For example, there’s 100 times more gold in a tonne of smartphones than in a tonne of gold ore. In 2022, the overall gross value of such metals contained in e-waste (before management) was estimated at US$ 91 billion. This highlights the importance of extending device lifecycles through circular technology solutions that help preserve valuable resources and reduce the need for new material extraction.

E-waste growing 5 x faster than documented recycling

Over the past few decades, technological progress has seen a notable rise in electronification, making it difficult to imagine daily life without various electronics. Linear consumption habits have fueled the need for constant upgrades, and to cater to the appetite for novelty, products with shorter lifecycles have entered the market. What has not kept the same pace is managing the growing amounts of e-waste.

According to the Global E-waste Monitor 2024, global e-waste amounted to around 34 billion kg in 2010. Growing by an average of 2.3 billion kg each year, it reached a record amount of 62 billion kg in 2022. During the same period, formal collection and recycling only increased from 8 billion kg to 13.8 billion kg — about 0.5 billion kg per year. This means, the generation of e-waste is expanding almost five times faster than formal recycling efforts, reflecting the growing imbalance between technological progress and global recycling volumes. The same source projects global e-waste to reach 82 billion kg by 2030. (Global E-waste Monitor 2024)

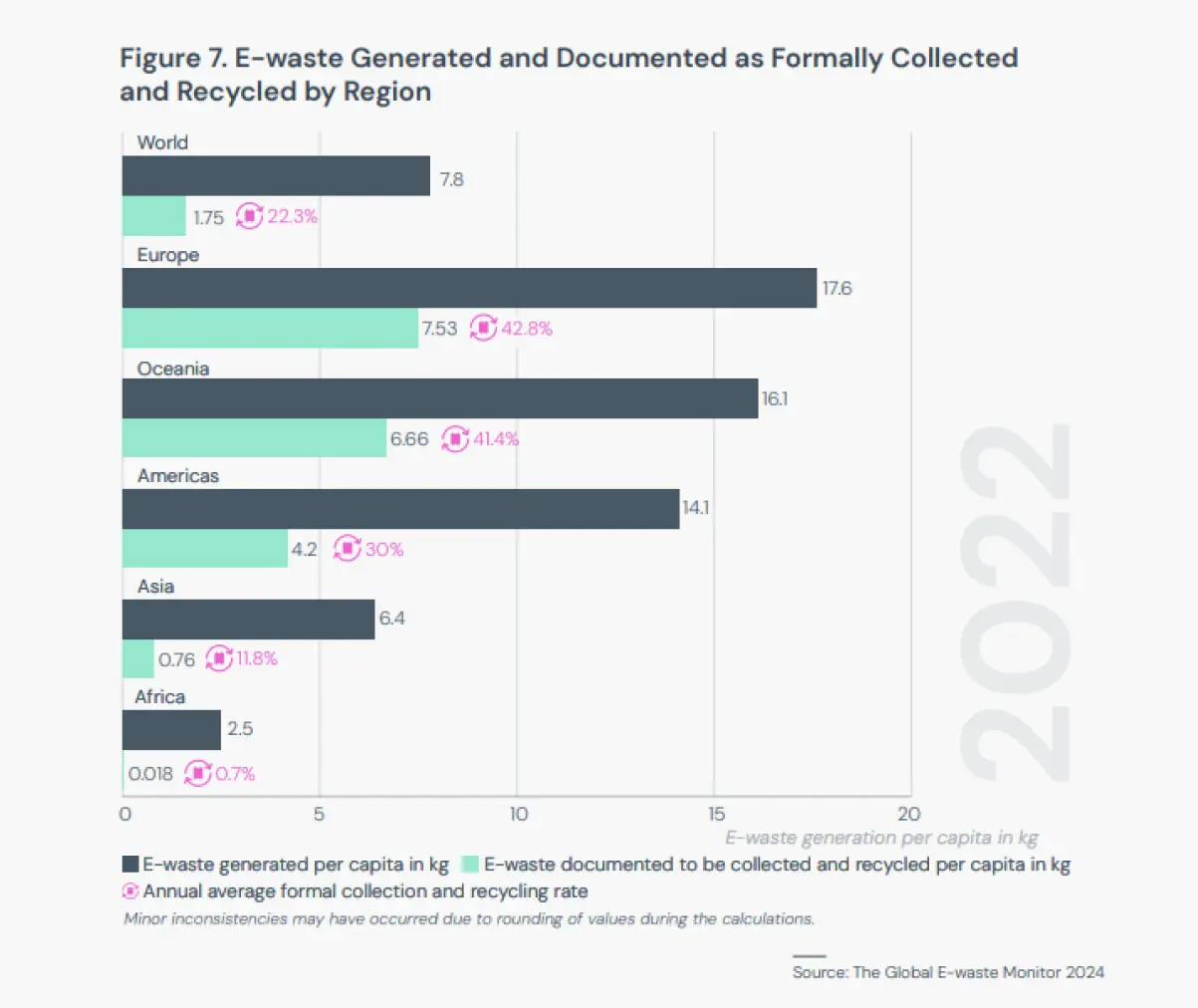

An average of 7.8 kg of e-waste per capita per year can already seem like a shocking amount, but differences in documented rates are just as notable. Europe leads in both e-waste generation and formally documented recycling rates, while the lowest have been documented in African countries.

The reasons behind the variations across regions are multifold: from general correlations between higher income levels and purchasing power, to legislation, regulations, and all the way to the overall maturity of formalized e-waste management systems. Regions with robust legal frameworks and developed infrastructure achieve higher formal collection rates, while in others, large volumes of e-waste are still handled informally or not documented at all. A large part of electronic waste generated gets processed in the respective region, yet studies estimate about 6% is still shipped in an uncontrolled manner to low- and middle-income countries where informal e-waste recycling activities may pose several adverse health effects.

While increasing formal recycling rates is important, halting and reversing the growing volumes of waste requires equally as much attention.

“The issue today is simply that not enough people return their devices. Devices are left to gather dust in drawers or end up in general waste. From a circular economy perspective, any return counts, because each device holds an opportunity for either reuse or material recovery. “

Taina Flink, Interim Chief Sustainability Officer at Foxway.

While the reasons behind low return rates can often be quite simple, the need to start recognizing the value in both end-of-use and end-of-life devices is evident.

Can e-waste be avoided?

By definition, materials never become waste in the circular economy. It comes down to the design of the value chain. Materials may exit one process as “waste” but become “resources” for another. As the Ellen McArthur Foundation puts it: in a circular economy, nature is regenerated, products and materials are kept in circulation and global challenges are tackled by separating economic growth and prosperity from the consumption of finite resources. It’s a system that breaks away from the linear “take–make–dispose” model and keeps products and materials in use for as long as possible, preventing waste and pollution.

In practice today, extending device lifecycles, improving repair and reuse systems, and recovering materials all help slow the generation of electronic waste, but they don’t eliminate it entirely. Even when fully embracing circular tech as a natural part of the value chains we have today, at one point the device will reach e-waste status. The question is how far we can extend the time from production to end-of-life and what can be done to support effective recycling afterwards.

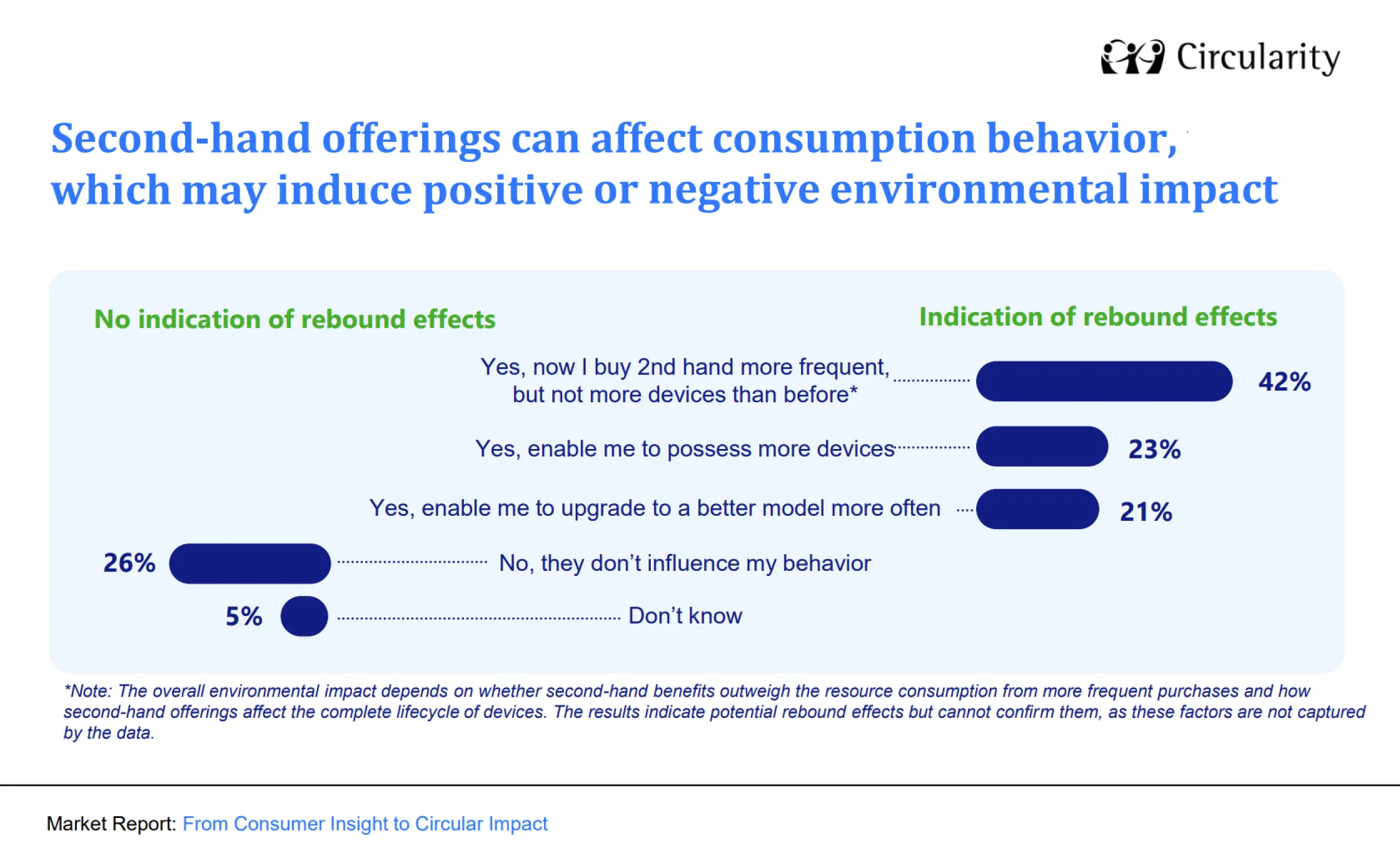

At the same time, each progress can also come with downsides. In 2024, Foxway contributed to a German study on circular business models in the tech sector, which revealed that:

- 42% of second-hand shoppers buy more often.

- 23% said they own more devices due to the availability of second-hand options.

- Rental models amplify this trend—41% of renters upgrade more frequently, and 39% rent devices they wouldn’t have otherwise used.

In addition, the growth of e-waste generation vs collection/recycling rates mentioned earlier shows that without an overall change or notable decrease in consumption, the existing coping mechanisms stand a slim chance of tipping the scales.

To make circularity truly effective and ensure that circular strategies can reduce the pressure on materials and ecosystems, it needs to be coupled with sufficiency. In the words of economist Tim Jackson “More is only better when there’s not enough”. To break free from the endless linear consumption patterns, we’d need to shift to a sufficiency paradigm that prioritizes high-quality products designed for longevity and ease of repair.

Enhancing sufficiency within circular systems offers a pathway toward an economy that operates within planetary boundaries and aligns with the realities of a resource-constrained world.

The role of circular tech companies in mitigating e-waste

Circular tech enablers like Foxway have a key role in reducing the negative environmental impact of the technology sector. By extending device lifetimes and keeping existing tech in use for longer, they offer a more sustainable alternative in catering to societies’ dependency on electronics. As valuable materials stay in circulation, there’s less need for producing new devices and extracting critical or rare earth minerals.

Their broader influence extends even further. Circular tech companies can shape how the market perceives value — highlighting that a device’s first use is only one stage of its full lifespan. Such companies challenge the notion of disposability and help normalize reuse as standard practice.

While the secondary device market has grown steadily year over year, the circular tech industry is witnessing a variety of challenges that require extensive collaboration for progress.

“Steps toward more circular systems are being taken, but progress is still slow. The circular economy is still fighting misconceptions that circularity is about recycling, both in legislation and in the business world. That’s because it’s the easy way out. It’s easy to legislate and it’s easy to send off your waste to a recycling facility. But the needle-shifting efforts manifest when business models become circular — building on refurbishment, reuse and longevity.”

Taina Flink, Interim Chief Sustainability Officer at Foxway

Engagement is crucial on all possible levels that shape market trends and consumer behavior. Associations like EUREFAS advocate for fair regulation, harmonized quality standards, and stronger recognition of refurbishment in EU legislation. Most existing legislation has been drafted from the perspective of new devices without considering whether the secondary market should be treated differently.

With continued active collaboration with policy makers, between businesses, and with a focus to influence consumer behavior, the circular tech industry can reshape how society interacts with technology. In doing so, it can turn resource efficiency and responsible consumption into lasting norms.

Sustainability